Friday, September 25, 2009

Parking Question

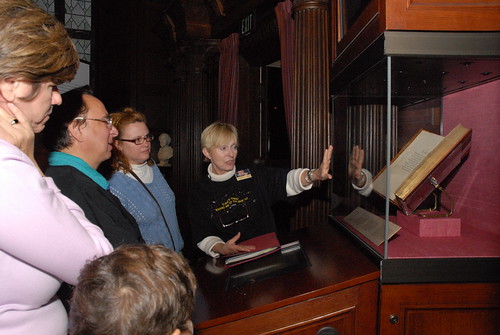

Hoitsma 2009 - An Evening with Barbara Mowat

“What do you do, correct Shakespeare’s grammar?”

“What do you do, correct Shakespeare’s grammar?”Barbara Mowat, co-editor of the Folger editions of Shakespeare’s plays, gets this question a lot at dinner parties. Recently retired as the Folger’s Director of Academic Programs, Barbara kindly returned to the Library to deliver the 2009 Hoitsma Lecture to a fascinated crowd of docents, answering this and many other questions about what it actually means to edit Shakespeare.

Any editor, she noted, bumps immediately into the fact that all Shakespeare’s manuscripts are completely missing. For plays that only come to us in the First Folio, there is nowhere to go when a word or phrase makes no sense. For other plays, which may have been published in one or more quarto editions as well as in the Folio, the textual narrative can get complicated indeed. In fact, every play has its own history, and it can be misleading to generalize about editing Shakespeare.

Exactly 300 years ago in 1709, the first known editor of Shakespeare’s work, Nicholas Rowe, published his edition. Barbara remains fascinated by the power of Rowe’s impact even today. In his effort to reconcile the four Folio editions and 70-some quartos published by his time, Rowe also regularized character names, inserted stage directions, and wrote Dramatis Personnae lists that persisted into the 20th century.

In fact, every edition reflects its editor’s reaction to prior editions. Over the course of the 18th century, editors after Rowe gravitated back to the First Folio, viewing quartos as stolen, bungled versions. The discovery that the Folio texts of Romeo and Juliet, Much Ado about Nothing, and Midsummer Night’s Dream were simply reprints of quartos published during Shakespeare’s lifetime led to serious exploration of quarto texts and editorial efforts to judge which are “good” and which “bad.”

In modern times, some editors have argued that Shakespeare himself wrote different versions of the same play at different points in his life, others that he merely revised and edited the plays throughout his career. The “New Bibliographers” believe that different versions reflect different manuscripts circulating for different purposes—prompt books, for example, in addition to published texts.

Barbara and her co-editor Paul Werstine feel that in the end “we cannot discern where the texts come from and we just have to work with everything that comes down to us.” They start with the First Folio text, modernize spelling and verb tenses, and consult other editions to resolve the inevitable questions that arise. Much work is in revising and updating explanatory notes, because earlier ones were written for a very different educational system, when knowledge of the Bible and classics was assumed. They began work on the new Folger editions in 1989, and the first six plays were published in 1992. The last, Two Noble Kinsmen, will appear in February 2010. The hardest play to edit? It was Othello, “because two very different texts come down to us, both disasters,” says Barbara. But each play offered some challenge, because ambiguities are still being discovered and debated.

In the end, the Shakespeare that is alive and beloved among us is the product of 400 years of different editions. “People are troubled and even offended that the Shakespeare they know is an editorial construct,” Barbara laughed. “They often say, ‘But I read him in the original!’ I like to think that if they knew how much love and care we editors lavish on the works, they might not mind so much.”

Friday, September 18, 2009

Imagning China with Timothy Billings Part 4

Q: You have said there are lots of excellent illustrations in China illustrata. Are we going to see them on the Folger Website?

A: Some are on the wall throughout this exhibit and on the Title cards for each case. Others will appear in the next Folger magazine.

Q: Your enthusiasm in contagious. Can you tell us how you got interested in this subject?

Then at Cornell he studied with Scott MacMillen, the great Shakespeare scholar. He felt that he had to choose between his two interests, WS and China; then discovered, maybe not. So it led to things like this exhibition. The FSL has a lot of material about the Early Modern European’s view of China, but it is not well known When Tim presented this idea to Gail Paster, her response was “Do we have any?”

A: Only one, in Measure for Measure, Act II, Scene 1 , Pompey is giving a long discursive answer to a question and includes “they are not China dishes, but very good dishes,” WS didn’t take any of his sources from China; he gets a lot from the Bible, from Plutarch, a completely different set of texts. He does use the word “Cathayan” to mean a liar. In this context, a “Cathayan” is a European traveler who has returned from China. Their unbelievable stories led to the general use of the word for someone who stretched the truth.

Q: When did the Chinese first learn about WS?

A: In the late 19th century, in connection with the Opium Wars, there was a transfer of history books into China. WS showed up in the context of history. As far back as the early 16th century, some Chinese went back to Europe with merchants, but most did not leave written accounts. There was one who lived in Paris and died apparently of heartbreak at being isolated from his country. He seemed to be of a melancholic disposition; it is a mistake to consider an individual as representing his whole culture; he is himself.

Chinese Dynasties

Jin Dynasty, 266 through 420 CE

Tang Dynasty, 618-907 CE

Yuan Dynasty, 1271-1368 CE, an occupying dynasty of Mongols

Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644 CE

Qing Dynasty (pronounced “Chin”), 1644-1911, a Manchu dynasty

Books Available at the Shop

Vermeer’s Hat: the Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World by Timothy Brook

Chinese Shakespeares by Alexander Huang, the Video Curator

On Friendship---One Hundred Maxims for a Chinese Prince by Matteo Ricci, translated and

introduction provided by Timothy Billings, the Exhibit Curator

The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci by Jonathan Spence, out of print, but recommended byJennifer Newton and endorsed by curator

Imagining China with Timothy Billings Part 3

This figurine has never been publically shown. It is not the sort of art that collectors collected. It is missing its cap and scepter; the scepter was probably made of jade... Upper right: A London edition of a Jesuit work with additional illustrations of what Chinese people looked like; the illustrations were copied from similar figurines brought back by English sea captains.

Case 8: Religion & Superstition

This 17th century porcelain figure shows the Great General and hero, Guandi. He is also shown in the engraving above the figure. Later, after his death, he was given the posthumous title of

Emperor. He was venerated; in fact. he became the most popular deity in the Daoist pantheon.

European writers don’t give Chinese religion a fair shake, but the information is detailed and

accurate when you filter out the cheap shots.

Case 9: Civilized Comforts

Two pairs of chopsticks, one of ebony and one of ivory. Matthew Ricci wrote that chopsticks were made of ebony and ivory, with silver tips. In one pair the silver is on the handle end; in the other the silver is on the eating end. Supposedly silver will reveal the presence of poison. The chopsticks are also borrowed items; one from the curator, one from an antique dealer.

Free Standing Case: Polyglot Bible

This Bible was printed in several languages. To set it apart from some other multilingual Bibles, the publisher wished to include some samples of other languages including Chinese. So they went to the Orientalist, Thomas Hyde, for a text that they included in their Bible. On the right is a facsimile of the page (now in the British Library) which was copied. A popular Chinese novel, The Romance of the three Kingdoms, had been dismantled and its pages acquired by various scholars who wanted an example of Chinese writing. This page is actually the last page of the novel, the colophon identifying the date and place of publication.

Case 10: Real Characters

In Europe there was much discussion among intellectuals about devising a Universal Language, something everyone in the world could speak. This would return us to the period before the Tower of Babel. These 16th and 17th century European philosophers believed that the Adamic or Edenic language, as they referred to the one first spoken in the Garden of Eden, was intimately connected with things in the real world; (as opposed the modern deconstructionists’ belief that words are merely arbitrary symbols). They tried to reconstruct or invent such a language so that the name of a thing would make clear where it fit into creation. As an example, the word for horse might consist of three parts; the first would indicate an animal, the second that it was a quadruped and the third be the specific kind of animal. They saw Egyptian hieroglyphics as an example of this. When they learned that Chinese written symbols involved combinations of several basic words, they welcomed that into their theories...Upper left: One wacky fellow named John Webb wrote a book claiming that Chinese was closest to the Edenic language because of its picture writing...

Lower right: John Wilkins was working from a sample of Chinese characters that looks nothing like real Chinese characters.

Case 11: Kong Fu Zi Says

This case is on Confucius, something we had to have in the exhibit. He was the Aristotle of Chinese culture and lived at about the same time. Matteo Ricci started trying to translate his work; the translation was very difficult and took centuries. Jesuits worked together on the translation...

Left: This very precious book is borrowed from the Library of Congress (the FSL does not own a copy.) The little round things shown on the table are ink stones, used to grind solid pieces of ink. Two characters appear over and over in the Chinese version; translated literally as “the master says” or as every Fortune cookie has it “Confucius says.”...Center. A 1573 Chinese edition of Confucius. This was written by the Grand Secretary as a simplified version to be read by the young emperor. So it was written as a more easily understandable edition to help him with his studies. The Jesuits used this to help them decipher Confucius. The writings of Confucius are hard to translate, especially when you have to write your own dictionary as you go along. In the 17th century there arise a huge controversy about Confucius, especially the fact that the Chinese apparently worshiped him. They paid homage to their deceased parents, to their ancestors and to great figures of history. Was this pious remembrance or worship? Matteo Ricci said it was a secular paying of respect, not worship; but others disagreed. By the time Ricci died, he had changed his mind. The custom was officially ruled to be worship and so incompatible with Christianity. “If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck” etc. This brought down the Jesuit mission since the Chinese wouldn’t give up their custom. By the early 18th century, the Jesuits were out of China. When they came back much later, they were redefined as missionaries.

Case 12:Imperial Letters

Case 13: A New Dynasty

This is the first of two cases related to drama. In 1644, the Ming Dynasty fell and was replaced by the Manchu Qing Dynasty which lasted until 1911 and was the last dynasty of China. This historical happening fascinated Europeans and became the source of a play written in 1676 by the up and coming dramatist Elkanah Settle, then the hottest thing on the English Stage. Some people claimed he was better than Dryden, but he turned out to be a flash in the pan while Dryden was ... Dryden. Settle’s play was not a bit historical or accurate. As was customary in the period, he included “tableaus” where the curtain would rise to show a number of actors in a still pose. One particularly dramatic one showed all the wives and concubines who had committed suicide (as ordered) after the overthrow of the old Emperor. That part of the story is true. Free

Standing Case: Chinese Translations of Shakespeare

By the early 17th century there were translations of WS’s works into German and French. By the mid 19th century, there was a great Japanese translation. In 1904 a Chinese scholar, a master of classical Chinese, translated some of the plays. He knew no English, but depended on a bilingual collaborator to tell him the stories. In turn, this collaborator was working, not from the original plays, but from a copy of Lamb’s Tales. Because of the excellence of the Chinese language, WS attained a very high reputation in China. The most popular stories (they were not translated as plays) were Hamlet and Macbeth because of the supernatural aspects. The title of the Chinese version is roughly “Strange Stories from across the Seas.”...The first translation of Hamlet as a play was in the 1920's. It was not until the 1960's that all the plays were translated. During the late 1930's and 1940's, there were two competing translators working; one affiliated with the Communists and the other with the Nationalists. During the Japanese occupation, they worked on the run. The Communist translator died after he had completed 30 of the plays. After the war, the Nationalist fled to Taiwan where he lived to an old age. The two translations are very different: one more oriented toward performance, the other toward a reading version. A individual’s preference is often based on his politics.

Case 14: The Orphan of China

The Yuan Dynasty was the Golden Age of Chinese drama. The Orphan of China was probably written around 1275. It was a variety play, like an operetta; colloquial speeches were interspersed with songs that are in a dense form of poetry and very hard to translate. For a Chinese audience these songs were very important, but they were sometimes omitted in the translations. It tells of a young man who survived the complete eradication of his family by a corrupt official. He became a hero, showing humor and nobility. At the end, he reveals the evil of the corrupt official; then chooses to turn him over to justice rather than taking personal vengeance. In 1735, it became the first Chinese play to be translated into a Western language, in this case French, and was included in a monumental work Description...de l’empire de la Chine. (This book is not in our exhibit)...

Upper left: Voltaire adapted the play into a work of his own. Also in the case are English translations of both the straight translation and of the Voltaire adaptation. David Garrick liked the play in the translation by Arthur Murphy and put it on at Drury Lane...

Upper right: There are lots of things we do not know about that production, but we do have the play bill...

Lower right. A letter from David Garrick to a friend about the play.

Imagning China with Timothy Billings Part 2

Lower right. China illustrata, a book so popular that this pirated version was published in 1667 by a Dutch printer. It is extensively illustrated; many of its illustrations are used on the wall and on the case cards throughout the exhibit. The author, Athanasius Kircher, was famous, a celebrity scholar. He wrote this, one of the most famous books on China, despite the fact that he had never been there and didn’t know a word of Chinese. He depended on material sent by the Jesuits in China.

Marco Polo had reported that there were communities of Nestorian Christians in China.

When the Jesuits arrived 300 years later, the Jesuits had hoped to contact them; but they had all disappeared. So when a stele, left by Nestorian missionaries, was discovered in 1625 in Xi’an

(where the terra cotta warriors were found.); it was particularly important to the Jesuits. ( A rubbing of the stele is on the wall to the right of the case.) The text is about Christian rulers and missionaries; the Jesuits spent decades working on the translation...Upper left. One of the most expensive books of the time, also by Kircher. The fold out shows the first Chinese text printed in

Europe. The text is from the Nestorian stele, but is not entirely accurate. It was engraved on a metal plate and printed like an illustration. With it are included two translations, one very literal, and lots of commentary by Kircher.

Free Standing Case

A copy of the original edition of China Illustrata belonging to Tim Billings. A pirated edition was

in Case 1.

Case 2: Friends and Collaborators

Matteo Ricci was a Jesuit who spent many years in China and learned to write in felicitous Chinese and to write beautiful Chinese characters. He was born in eastern Italy and died in 1610 so next year will be the 400th anniversary of his death. He had a Chinese friend, “Paul” Xu Guangq, who helped him with the language...Upper right. In answer to a question, Ricci wrote an

eloquent “Essay on Friendship” in Chinese; based on classical European sources, such as Aristotle and Plutarch. It was very popular and circulated widely in manuscript. Two of Ricci’s friends, independently, arranged to have his treatise published. He proclaimed loudly that this was without his knowledge and consent because if a Jesuit wished to publish anything, he had to have permission (a lengthy process that required approval from Europe.) This printed book became an instant best seller in the late Ming dynasty. He was invited to court and would have met the emperor, but by this time the emperor lived in total seclusion, seeing only his eunuchs. The emperor loved the mechanical clocks that Ricci gave him. He also loved the harpsichord that Ricci had ordered from Europe and taught one of the eunuchs to play. Ricci even wrote a piece of music to be played for the Emperor. (The Folger Consort will play this piece at their next concert.) The manuscript for this music was only discovered in 2000 AD among the papers of the Earl of Guilford, who had lived in Italy in the 17th century...

Lower left: Ricci attempted to translate Euclid’s Geometry into Chinese, but found it too difficult. Later with the help of his friend “Paul” , he was able to complete it. Upper left: Marco Polo had visited during the Yuan Dynasty; this dynasty was an occupying one of Mongols so he learned the Mongolian, not Chinese, names for places. He called China “Cathay” and used Mongolian names for the major cities as well. The word “China” comes from the Qing (pronounced “Chin”) dynasty that took power in 1644. Early maps showed Cathay and China as two separate places. The early Jesuits knew they were in “China” and kept looking for “Cathay”. Ricci was the one who definitely concluded that China and Cathay were one and the same.

Question: Is the Jonathan Spence book still considered a good source? It is a wonderful read.. {It is a biography of Ricci with a lot of information about the time and places in which he lived. See

book list at end of write-up. SPR}

Answer: Yes, Tim thought at the time that it had covered everything, but when he started work, he found out more. After these two cases, it is easy to make fun of the misconceptions the Europeans had about China.

Case 3: In Search of the Silkpeople

Case 4: The Great Walls

Here is where we begin the theme of what Europeans thought of when they thought of China. Freestanding Case This copy of Theatrum orbis terrarum is one of Tim’s favorite books in the exhibit. It is open to a map of China; in the lower right are some of the famous land ships, little sailing wagons or carts that were one of the first associations anyone in Europe had with China.

Over Case 5

Around 1600 AD a Flemish engineer built such a wagon, based on the description of the Chinese ones. It was not very successful since it tipped easily and was hard to steer. A fine example of a cross-cultural conversation. In fact, there were no such sailing wagons in China. A single reference from the 4th or 5th century shows a wheel barrow equipped with a sail.

Case 5: Cany Wagons Light

Center: A map by John Speed shows little sailing wagons in the upper left. Like his maps of European countries, he shows small pictures along the side of men and women dressed in their native clothing...Left: John Milton’s Paradise Lost is open to the page with the quote “With Sails and Wind thir canie Waggons light” referring to the Chinese sailing carts. On Wall: Strange Wonders In European reports of China, it is (and was) hard to separate what was real from what was crazy. They believed that there were no beggars in China. Some things were partly true. There was a picture showing fishermen lying back in a boat while birds caught the fish and dropped them into the boat. Most people considered that a legend. But later they learned about the trained cormorants who had rings around their necks to prevent them from swallowing the fish and who did bring them to the fishermen.

Case 6: Chinese Tales: Marco Polo’s Legacy

Lower right: This edition of Marco Polo has only one illustration; it shows a stalk of rhubarb! This kind was called the true rhubarb, unlike the kind found in Europe. It was held in high esteem as a medicine, very effective in purging. When Europeans thought of China, they thought of musk, rhubarb, sailing wagons and the Great Wall. Surprisingly, they did not associate silk with China. The best silk came from Italy. In early years, the Chinese had carefully guarded the secret of how silk was made. In the 6th century the Emperor Justinian sent some Jesuit missionaries to China to discover the secret. They carried bamboo walking sticks. They concealed larva of silk worms and mulberry leaves inside the hollow sticks and walked with them back to Rome to present them to the Pope. Thereafter silk was considered as Italian.

On Wall: Musk deer

Musk was a priceless commodity, used both in perfume and as a very popular medicine, used in cases of epilepsy among other conditions. It shows up in a lot of European medical texts.

Case 7: New Medicine

Visitors will be surprised at how open the Europeans were to acupuncture...Upper left. A 17th century European text based directly on a Chinese medicinal text. In the 1670's the Royal society devoted a session to discussing the efficacy of Chinese medicine. We’re not looking at straightforward progress from A to A+1. Remember, European medicine of the time believed in bleeding and the balance of humors so was similar in principle to Chinese medicine. The 16th and 17th century Europeans had a different set of assumptions about China than we do.

End Case: China Dishes

Imagining China: The View from Europe, 1550-1700 Overview given by curator Timothy Billings Part 1

Introduction:

the consultant on the preparation of this exhibit.

Materials: There is neither a catalogue nor a free brochure for this exhibit. There is material on the Folger Website and a cell phone tour, somewhat briefer than usual. (Phone number for the cell phone tour: (202)595-1844. There will be an article in the Folger magazine which will arrive soon. At the Information Desk, there is also a Children’s Guide, with a related page to take home.

Sources: Most of the books and documents in the exhibit are from our collection. A few rare

Chinese books and documents are borrowed from the Library of Congress or private owners (one of them is the Curator) or are facsimiles of things in other collections. Most of the Porcelain is from the Walters Gallery in Baltimore; about half is usually on exhibit and half is in storage there. Some of these pieces have never before been publicly shown.

Dynasties: For those of us with a very limited grasp of Chinese history, I have put a list of

dynasties and dates at the end of this write-up. Case Title Cards: The Chinese characters following the English titles are translations of the English titles (more or less.) Most of the pictures on the cards are taken from China illustrata; small print at the bottom identifies the source of each illustration. A few previous exhibits have used illustrations on the Title cards; this is the first time that identifying information has been used as well.

Overview

He asked us how much time we usually spent on the exhibit during our regular tours. When he heard “five to fifteen minutes”, he said he would go around and give us an idea of some

themes that he wished to highlight with this exhibit.

From the 1550's to the early 1700's, Europe looked at China with awe and admiration. By the mid 18th century, a negative tone crept in which led to the racist ideas of the 19th century. The Jesuit scholars who lived in China and learned the language really understood the society. But when their writings were translated and filtered through European biases, much misinformation crept in. He compares it to the game of “telephone” in which the message at the end bears little resemblance to the one at the beginning. (Cases 1 and 2) When Europeans of this period thought of China, they first thought of Rhubarb!, of sailing wagons, of musk and of porcelain. Except for porcelain, very different ideas than we have today. (Cases 5, 6 and 7)

The Jesuit mission ended because of a dispute about ancestor worship. The Chinese venerated with incense their own deceased parents, their ancestors and certain revered people of past times. One of these was Confucius. Was this proper respect or a type of worship incompatible with Christianity? The Pope finally ruled that is was worship, but the custom was so ingrained in the culture that it was Christianity that lost out. (Cases 8 and 11)

Cases 13 and 14 and the computer display show how Chinese history and Chinese plays were a source for European plays. Also Chinese translations and productions of Shakespeare’s plays.